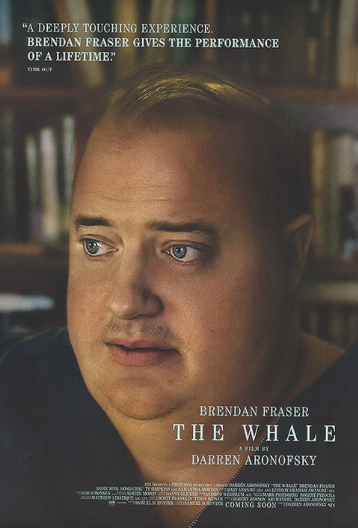

Let’s start with facts: The Whale, directed by Darren Aronofsky and adapted from the stage play by Samuel D. Hunter, is a dramatic bottle-episode of a movie starring Brendan Frasier as Charlie, a reclusive man teaching literature online who, finding himself facing mortality, wishes to reconnect with his estranged daughter. The only other people to make an appearance are Liz, Charlie’s only friend and occasional caregiver, Thomas, an earnest and nervous young man hawking religious ideology at the door, and a brief appearance by Mary, Charlie’s ex-wife. Oh, and there is an even briefer pop in by Dan the Pizza Delivery Man.

The movie took place entirely in Charlie’s house, mostly his living room. He never leaves, but through his interactions with Thomas, Ellie and Liz we get the picture of Charlie’s past which reveals the trauma that caused him to retreat in the first place. Kept from his daughter, rejected by religion, mourning the loss of a lover and questioning his place in it all, Charlie became depressed and disappeared from the world. He’s sweet and shy and used to being on his own. It is a picture of the complicated world that surrounds a depressed person and how no one knows how to approach or attempt to help a person in despair.

Instead, many viewers and reviewers of this movie reduce it to a story about fat.

There wasn’t anything wrong with The Whale. I thought it was moving, beautifully acted, and meticulously well-paced. There was however, something wrong with the audience and unfortunately it will take more than a movie to change that. To illustrate what I mean, we need to talk about the chicken. Early in the film, Charlie eats a piece of fried chicken – one single piece of fried chicken is eaten on camera. In fact, he doesn’t even finish it, he takes three bites. When this happened, the audience in my theater gave an audible groan of disgust. The eating of fried chicken caused a reaction like the bloodiest Tarantino.

What made this more meaningful was that I saw The Whale at a festival where it was directly followed by a screening of White Noise, the dark comedy directed by Noah Baumbach. There was a lot going on in White Noise, but of particular interest to me now is a dinner table scene in which Adam Driver ate, again, a piece of fried chicken. Most interesting – no one in the audience made a sound. In addition, I’ve heard the chicken-eating in The Whale described repeatedly with phrases like “joylessly wolfs down”, “gobble greasy fried chicken straight from the bucket” (I’m sorry, do you get a plate for your KFC?), “gorge”, “going at”, or “greasy chomping” but again – Charlie takes a few bites of one piece of chicken. Just like Adam Driver. Just like any human who eats a piece of chicken.

What was different? Charlie was obese. When he ate, it repulsed people. Adam Driver’s character was styled as a middle aged, suburban academic with oversized glasses and dull sweaters. But he wasn’t obese, so he was permitted to eat. We don’t want fat people to eat at all, as if they could simply decide to abstain from eating entirely until they lose weight. Most recaps or reviews I saw of The Whale open with a physical description of Charlie; you will likely find the movie described as being about a really fat guy, the assumption being that he is a recluse because he is fat (and why wouldn’t he be, if everyone loses their mind over his interaction with a single piece of chicken?). But that isn’t why Charlie is a recluse. He retreated from pain after being kept from his daughter, restarting his life, watching his lover suffer and struggle with rejection from the religion he was raised with and ultimately, losing him to suicide. Charlie wasn’t dying of obesity. Charlie was dying of depression.

By the time Charlie eats that piece of fried chicken, food choices are far from the problem. No salad or jogging routine will improve his health, and any intervention needed to start long before, when he began to retreat in emotional pain. We don’t see that time in his life, just like we don’t see all those factors when we meet a fat person in the real world, and the movie itself slowly reveals his history and trauma. What comes to light is a laundry list of depression factors: a breakup of a marriage, realization of sexual identity, severing of a father-daughter relationship, rejection from a religious group, and finally loss of a lover.

Did Charlie kill himself, or was Charlie trying to live under impossible circumstances, without support? He had lost so much, and isolating can feel like reengineering, focusing on yourself so you can emerge better, or at least heal in private, without being vulnerable to a world that has already been so careless with you. And food can be a comfort in this time, maybe the only thing that brings peace when everything else you relied on has brought pain. And slowly it gets away from you – time to heal has become time in hiding, and feeding the pain becomes indulging it, and you don’t know when that started. Can you imagine that much pain?

For this reason, I think it is brilliant that The Whale takes place over only a few days at the point in Charlie’s life where this damage has already been done. No decisions can be made now – the turning point (if it was ever a unique moment, and not a grey blur of depressed weeks or months) is long past. If we truly consider these circumstances, judging Charlie for his predicament is lazy and mean. The social world of friends, religion and healthcare failed him long ago, and the audience fails this movie now if they reduce his plight to his final moments, instead of considering the long descent his dark pit implies.

Charlie’s decision to retreat is reinforced and confirmed for him as right through his interaction with the Pizza Delivery Man. A few times, Charlie orders pizza and when it arrives the delivery man slowly makes greater efforts to be friendly instead of simply leaving his delivery on the porch. He calls through the door, introduces himself, asks Charlie his name and if he’s ok…he is a nameless voice, tentatively reaching out with what might be kindness. This offers a chance for humanity, as represented by Dan the Pizza Delivery Man, to redeem themselves in their treatment and abandonment of Charlie. For me, this opportunity is the one incongruent part of an otherwise tight story of isolation and depression. I don’t believe the Delivery Man calls out. He does not introduce himself, and he does not ask your name. As Thomas Hardy said, “Nobody came. Because nobody ever does.”

But maybe in this story he did need to come, just to show the audience one last time that human kindness will fail, when Charlie finally does open the door and the Delivery Man, upon seeing his physical presence, turns and leaves in disgust. Faced with Charlie, knowing nothing about him except his pizza preferences and his appearance, his kindness was withdrawn. He was just a poor lonely guy until – he was fat. Then he was a monster. Just like the audience turns on him when he disgraces himself by eating chicken. He could only have gained sympathy if he had tried harder not to take up so much space. So it is all the more insulting that the audience cries over what they view to be his killing himself with food; you wanted him to take up less space. He heard your message, and prepares to oblige.

I think the message to be found in The Whale is about what we don’t do for people, how individuals and society neglect those that don’t meet our standards as deserving of help, support, love or grace. We deny them, then hold them responsible for how they end up. We see this story in the results of systematic racism, sexism, incarceration and of course, physical and mental health. No one ends up in Charlie’s state overnight. When the gut reaction to judge hits, The Whale asks us that we stop and ask ourselves what we might have done for him years before. Who around you today isn’t getting the help, support or care that might prevent them from closing the door on their connections, and would you even notice before it’s too late?